Editor's note: This is part of a series of reports CNN.com is featuring from an upcoming, six-hour television event, "God's Warriors," hosted by CNN chief international correspondent Christiane Amanpour.

(CNN) -- Last year at Christmastime, Rehan Seyam, a Muslim living in New Jersey, went to pick up some things at a local Wal-Mart. Seeing her distinctive traditional Muslim head covering called a "hijab," a man in the store, addressing her directly, sang "The 12 Days of Christmas" using insulting lyrics about terrorism and Osama bin Laden.

She was stunned.

"Do I look like a terrorist to you?" Seyam said she asked the man.

According to Seyam, the man replied, "What else does a terrorist look like?"

Such stories are not altogether uncommon for Muslim Americans. According to a recent poll by the Pew Research Center, 53 percent of Muslims living in America said it has become more difficult to be a Muslim in the United States since the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Fifty-one percent said they are "very worried" or "somewhat worried" that women wearing the hijab are treated poorly, according to the poll.

A simple headscarf generally used by women to hide the hair from view, the hijab has become so controversial among some that several countries have banned or considered banning Muslim women from wearing them in public places. In light of this contentiousness, why do Muslim women choose to wear the hijab? Watch the making of CNN's TV special "God's Warriors" »

Gayad al-Khalik lives in Egypt and says the hijab is a focus on inner beauty.

"I want to shift the attention from my outer self to my inner self when I deal with someone, I don't want them to look at me in a way that wouldn't suit me," she told CNN in an upcoming documentary called "God's Warriors."

Al-Khalik is fluent in English and German; studied in Europe; plays Western music on her guitar; and spent time working for a women's rights organization.

She wears the hijab -- and says it's not just for religious reasons.

"My own conclusion was it is debatable whether it is a religious obligation or not, but I chose to keep it on because I do believe in modesty and you shouldn't be showing off yourself," al-Khalik said.

The Quran calls for women to be modest in their dress but interpretation of the edict varies widely, according to religious experts who spoke with CNN. An author who has written widely on Islam told CNN the Quran does not require women to wear the hijab.

"There's nothing in the Quran about all women having to be veiled or secluded in a certain part of the house. That came in later [after Prophet Mohammed's time]," said religious historian and author Karen Armstrong.

For Seyam, the hijab is a religious duty. "It's God's wish," she said.

"It's a requirement by God. He wants us to cover. He wants us to be modest," Seyam said.

But as important as the hijab is to her, Seyam's decision to cover her face wasn't one she made easily.

"It was very dramatic for me. And I remember, even now thinking about it, it really does make my heart beat a little bit faster," she said, "I was making a decision I knew was permanent. You put on hijab, you don't take it off."

Through her childhood growing up in Long Island, New York, Seyam prayed with her devout Muslim parents, but says she was just "going through the motions." It wasn't until college that she decided to wear a hijab consistently.

Influenced by her more devout friends, Seyam decided being a good Muslim meant covering her head.

"My sole purpose is to be here for the sake of Allah, and I'm doing something that he specifically says that you should be doing."

Seyam said there were practical factors in her decision as well. "I'm sick of guys catcalling. It was just driving me crazy. I felt like a piece of meat."

But Seyam says she traded in catcalling for a different kind of negative attention. People "look at me as if I am threatening and I do not feel like I am threatening looking. I don't feel I should instill fear in anybody's heart, but I do feel like I get dirty looks," she said.

Still, Seyam says her faith sustains her and that wearing the hijab is an important part of that faith.

"I'm not here to live my life and do whatever I want. I'm here to worship God," Seyam said. "I don't think that everybody has that, and I think that I'm lucky for it."

By Brian Rokus CNN 08/21/2007

http://www.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/meast/08/21/hijab.godswarriors/index.html

22 August 2007

10 August 2007

Jordan Yields Poverty and Pain for the Well-Off Fleeing Iraq

AMMAN, Jordan, Aug. 9 — After her husband’s killing, Amira sold a generation of her family’s belongings, packed up her children and left behind their large house in Baghdad, with its gardener and maid.

Now, a year later, she is making meat fritters for money in this sand-colored capital, unable to afford glasses for her son, and in the quiet moments, choking on the bitterness of loss.

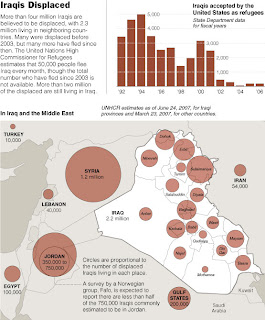

The war has scattered hundreds of thousands of Iraqis throughout the Middle East, but those who came here tended to be the most affluent. Most lacked residency status and were not allowed to work, but as former bank managers, social club directors and business owners, they thought their money would last.

It has not. Rents are high, schools cost money, and under-the-table jobs pay little. A survey of 100 Iraqi families found that 64 were surviving by selling their assets.

Now, as a new school year begins, many Iraqis here say they can no longer afford some of life’s basic requirements — education for their children and hospital visits for their families. Teeth are pulled instead of filled. Shampoo is no longer on the grocery list.

“My savings are finished,” said Amira, who is 50. “My kids won’t be in school this year.”

It is a painful new reality for an important part of Iraq’s population, the educated, secular center. They refused to take sides as the violence got worse. And their suffering augurs something larger for Iraq. The poorer they grow and the longer they stay away, the more crippled Iraq becomes. “The binding section of the population does not exist anymore,” said Ayad Allawi, a former prime minister, who now spends most of his time in Jordan. “The middle class has left Iraq.”

Iraqis streamed into Jordan and Syria in 2005 and 2006, with the professional class picking Jordan. The signs on the second floor of Al Essra Hospital, a private hospital in central Amman, display only Iraqi doctors’ names. The Jordanians have been relatively lenient, registering doctors in their medical unions and allowing the vast majority to live in their country without residency permits.

But by early this year Iraqis were weighing so heavily on this small country that the Jordanian authorities sharply reduced the numbers they accepted. (Rejections became so common that Iraqi Airways now offers a 30 percent discount to returning passengers who have been turned away.)

Many thought Jordan would be a stop on the way to Australia or Sweden, or a brief vacation from Baghdad’s inferno. But as the months wore on, it became clear that most countries were closed to Iraqis, the war was only getting worse, and families were left stranded, burning through their savings. The Australian authorities twice rejected Hassan Jabr, a Spanish teacher who left his elegant home and garden in Baghdad after his 12-year-old son was kidnapped and killed last year. Now, with his savings gone, badly dented before he left by a $10,000 ransom that he paid to try to get his son back, he is living off his family’s food ration cards that his mother sells in Baghdad.

“We saw reality in Amman and we were shocked,” he said, sitting in his spare one-room apartment in eastern Amman. “We planned for two months.”

Iraqis here have never been formally counted. A survey by a Norwegian group, Fafo, which has not been made public, is expected to report there are less than half of the 750,000 commonly estimated to be in Jordan.

But that is still 10 percent of the population of two million in Amman, where most of the Iraqis live, and aid agencies have stepped up activities.

This month the Jordanian government, under pressure from the United States, agreed to let Iraqi children without residency attend public schools, a right not extended to any other foreigners.

But the schools are crowded and the government has not yet prepared for the change, arguing that it should receive aid to accommodate it. United Nations agencies are asking for extra money to expand, at first by adding new shifts to existing schools.

Save the Children, a humanitarian group, says it has referred 4,000 Iraqis to schools recently, but the referrals do not guarantee acceptance. Amira went to the public school in her neighborhood, but was told that there was no room for her children. Private school cost her $5,000 last year, a third of her savings.

As the middle class becomes poor, new patterns form. Zeinab Majid’s okra stew no longer has meat. She buys her vegetables just before sunset, when the prices are the lowest. A stranger offered her the use of a washing machine, a gesture that nearly brought her to tears.

She came to Amman last September after her husband, a painter, had received two threats, and the studio he used had been bombed. They sold everything. Now her husband, a quiet man in small round glasses, spends his days jabbing paint onto small canvases while their boys, ages 7 and 4, watch cartoons on an old TV. “There are days when I’m penniless completely,” she said, serving juice to visitors. A Catholic relief organization, Caritas, helped pay for first grade for her older son last year.

The pain of the war closes people, and recent arrivals tend to live isolated lives, dividing the community into small, sad pockets. Amira moves mechanically through her days like a stunned survivor of a shipwreck. Tears come easily when she remembers the belongings she sold, the photo albums she did not take. Her husband, a Sunni, died five days after men in police uniforms took him from his shop last year. His face was bruised and his body broken. It was 22 years to the day since they first met.

“They were after the happiness,” she said, her face wet with tears. “They wanted to kill the happiness.”

The United States promised to increase the number of Iraqi refugees it takes, and the United Nations has referred 9,100 Iraqis to it this year. But so far fewer than 200 have arrived, according to the State Department. Several hundred more are expected to arrive in the coming weeks.

Running out of money is frightening, and some families choose to move to Syria, where things are cheaper, or, in some cases, back to Baghdad and the war.

Aseel Qaradaghi, a 25-year-old software engineer, was pregnant when she brought her small daughter here last summer after receiving threats from Islamic extremists. Her husband, a translator for a South African security firm, stayed in Baghdad to earn money. But when he did not call on her birthday, she knew something was wrong, and only after pressing his friends on a crackling phone line did she learn that he had been kidnapped.

Now, eight months later, she is earning a small wage at a nursery, but without his salary it is not enough, and she has applied for refugee status. If she is rejected, she will have to return to Baghdad. She does not know her husband’s fate, but worries that it will be the same as her brother’s, killed for working as a translator for the American military.

“I cannot allow myself to think about him,” she said, bouncing her baby boy on her lap. “The moment I start to allow feelings, my life will stop. I’m afraid of the moment that I collapse.”

Last week, Amira had a guest. Nada, a mother of three, whose husband worked as a deputy director of a prestigious social club in Baghdad, was preparing to move to Syria. The thousands of dollars from the sale of several cars and a house are almost gone.

“My daughter was second in her class,” Amira said, her words coming hard and fast. “I traveled all over the world. I want to tell the Americans what has happened to us.”

Yusra al-Hakeem contributed reporting. New York Times 08/10/07

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/10/world/middleeast/10refugees.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

Now, a year later, she is making meat fritters for money in this sand-colored capital, unable to afford glasses for her son, and in the quiet moments, choking on the bitterness of loss.

The war has scattered hundreds of thousands of Iraqis throughout the Middle East, but those who came here tended to be the most affluent. Most lacked residency status and were not allowed to work, but as former bank managers, social club directors and business owners, they thought their money would last.

It has not. Rents are high, schools cost money, and under-the-table jobs pay little. A survey of 100 Iraqi families found that 64 were surviving by selling their assets.

Now, as a new school year begins, many Iraqis here say they can no longer afford some of life’s basic requirements — education for their children and hospital visits for their families. Teeth are pulled instead of filled. Shampoo is no longer on the grocery list.

“My savings are finished,” said Amira, who is 50. “My kids won’t be in school this year.”

It is a painful new reality for an important part of Iraq’s population, the educated, secular center. They refused to take sides as the violence got worse. And their suffering augurs something larger for Iraq. The poorer they grow and the longer they stay away, the more crippled Iraq becomes. “The binding section of the population does not exist anymore,” said Ayad Allawi, a former prime minister, who now spends most of his time in Jordan. “The middle class has left Iraq.”

Iraqis streamed into Jordan and Syria in 2005 and 2006, with the professional class picking Jordan. The signs on the second floor of Al Essra Hospital, a private hospital in central Amman, display only Iraqi doctors’ names. The Jordanians have been relatively lenient, registering doctors in their medical unions and allowing the vast majority to live in their country without residency permits.

But by early this year Iraqis were weighing so heavily on this small country that the Jordanian authorities sharply reduced the numbers they accepted. (Rejections became so common that Iraqi Airways now offers a 30 percent discount to returning passengers who have been turned away.)

Many thought Jordan would be a stop on the way to Australia or Sweden, or a brief vacation from Baghdad’s inferno. But as the months wore on, it became clear that most countries were closed to Iraqis, the war was only getting worse, and families were left stranded, burning through their savings. The Australian authorities twice rejected Hassan Jabr, a Spanish teacher who left his elegant home and garden in Baghdad after his 12-year-old son was kidnapped and killed last year. Now, with his savings gone, badly dented before he left by a $10,000 ransom that he paid to try to get his son back, he is living off his family’s food ration cards that his mother sells in Baghdad.

“We saw reality in Amman and we were shocked,” he said, sitting in his spare one-room apartment in eastern Amman. “We planned for two months.”

Iraqis here have never been formally counted. A survey by a Norwegian group, Fafo, which has not been made public, is expected to report there are less than half of the 750,000 commonly estimated to be in Jordan.

But that is still 10 percent of the population of two million in Amman, where most of the Iraqis live, and aid agencies have stepped up activities.

This month the Jordanian government, under pressure from the United States, agreed to let Iraqi children without residency attend public schools, a right not extended to any other foreigners.

But the schools are crowded and the government has not yet prepared for the change, arguing that it should receive aid to accommodate it. United Nations agencies are asking for extra money to expand, at first by adding new shifts to existing schools.

Save the Children, a humanitarian group, says it has referred 4,000 Iraqis to schools recently, but the referrals do not guarantee acceptance. Amira went to the public school in her neighborhood, but was told that there was no room for her children. Private school cost her $5,000 last year, a third of her savings.

As the middle class becomes poor, new patterns form. Zeinab Majid’s okra stew no longer has meat. She buys her vegetables just before sunset, when the prices are the lowest. A stranger offered her the use of a washing machine, a gesture that nearly brought her to tears.

She came to Amman last September after her husband, a painter, had received two threats, and the studio he used had been bombed. They sold everything. Now her husband, a quiet man in small round glasses, spends his days jabbing paint onto small canvases while their boys, ages 7 and 4, watch cartoons on an old TV. “There are days when I’m penniless completely,” she said, serving juice to visitors. A Catholic relief organization, Caritas, helped pay for first grade for her older son last year.

The pain of the war closes people, and recent arrivals tend to live isolated lives, dividing the community into small, sad pockets. Amira moves mechanically through her days like a stunned survivor of a shipwreck. Tears come easily when she remembers the belongings she sold, the photo albums she did not take. Her husband, a Sunni, died five days after men in police uniforms took him from his shop last year. His face was bruised and his body broken. It was 22 years to the day since they first met.

“They were after the happiness,” she said, her face wet with tears. “They wanted to kill the happiness.”

The United States promised to increase the number of Iraqi refugees it takes, and the United Nations has referred 9,100 Iraqis to it this year. But so far fewer than 200 have arrived, according to the State Department. Several hundred more are expected to arrive in the coming weeks.

Running out of money is frightening, and some families choose to move to Syria, where things are cheaper, or, in some cases, back to Baghdad and the war.

Aseel Qaradaghi, a 25-year-old software engineer, was pregnant when she brought her small daughter here last summer after receiving threats from Islamic extremists. Her husband, a translator for a South African security firm, stayed in Baghdad to earn money. But when he did not call on her birthday, she knew something was wrong, and only after pressing his friends on a crackling phone line did she learn that he had been kidnapped.

Now, eight months later, she is earning a small wage at a nursery, but without his salary it is not enough, and she has applied for refugee status. If she is rejected, she will have to return to Baghdad. She does not know her husband’s fate, but worries that it will be the same as her brother’s, killed for working as a translator for the American military.

“I cannot allow myself to think about him,” she said, bouncing her baby boy on her lap. “The moment I start to allow feelings, my life will stop. I’m afraid of the moment that I collapse.”

Last week, Amira had a guest. Nada, a mother of three, whose husband worked as a deputy director of a prestigious social club in Baghdad, was preparing to move to Syria. The thousands of dollars from the sale of several cars and a house are almost gone.

“My daughter was second in her class,” Amira said, her words coming hard and fast. “I traveled all over the world. I want to tell the Americans what has happened to us.”

Yusra al-Hakeem contributed reporting. New York Times 08/10/07

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/10/world/middleeast/10refugees.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

06 August 2007

Olmert, Abbas meet on Palestinian soil

Israeli PM is first to visit a Palestinian city since fighting began 7 years ago

JERICHO, West Bank - Ehud Olmert on Monday became the first Israeli prime minister to visit a Palestinian town since the outbreak of fighting seven years ago, meeting under heavy guard with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas in Jericho to talk about the creation of a Palestinian state.

Olmert took a security risk in coming to the biblical desert town, but also gave a symbolic boost to Abbas, who stands to gain stature by hosting Olmert on his own turf.

Accompanied by two helicopters, Olmert arrived by motorcade at a five-star hotel just a few hundred yards from a permanent Israeli army checkpoint on the outskirts of Jericho.

The meeting was held in one of the West Bank’s most peaceful areas. However, it still posed a challenge to Olmert’s security detail, since the West Bank cities are controlled by Abbas’ weak police forces, which in June failed to prevent Hamas militants from seizing the Gaza Strip by force.

The meeting also tested renewed Israeli-Palestinian security coordination in the West Bank, following the fall of Gaza to Hamas. The Israeli army sealed checkpoints around Jericho, while Palestinian police blocked roads around the hotel.

Conflicting expectations

The Abbas-Olmert meeting is one in a series of sessions, meant to prepare for an international Mideast conference in the U.S. in November.

However, both sides appear to have conflicting expectations.

The Palestinians hope the two leaders will sketch the outlines of a final peace deal, to be presented to the U.S. conference, Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat said Monday.

The four core issues of a future peace deal are the final borders of a Palestinian state, a division of Jerusalem, a removal of Israeli settlements and the fate of Palestinian refugees.

“What they need to do is to establish the parameters for solving all these issues,” Erekat said. “Once the parameters are established, then it can be deferred to experts” for drafting.

However, David Baker, an official in Olmert’s office, said the core issues would not be discussed now.

The leaders will discuss humanitarian aid to the Palestinians and Israeli security concerns, as well as the institutions of a future Palestinian state, Baker said.

Baker said the meeting is a signal of Israeli good will, adding that Olmert “intends for this to be a productive meeting to enable progress with the Palestinians.”

Effort to ease West Bank life

Both sides said the meeting also will deal with easing daily life in the West Bank, including the removal of some of the checkpoints erected after the outbreak of the second Palestinian uprising in September 2000.

Abbas and Olmert previously agreed to try to restore the situation to what it was before the uprising, including returning full Palestinian control over West Bank towns and cities.

However, the Israeli military has been slow to dismantle roadblocks or ease control over Palestinian towns, citing concerns that Abbas’ forces are not strong enough to prevent attacks on Israelis.

Illustrating the issue, Olmert’s motorcade passed through one of the army’s checkpoints, at the entrance to Jericho. The checkpoint was erected after the outbreak of the uprising, and has controlled Palestinian traffic in and out of the town ever since, often causing long delays for motorists.

Symbol of a bygone era of optimism

The Abbas-Olmert meeting place is surrounded by symbols of a bygone era of optimism, as well as the failures of peace talks. Across the street from the Intercontinental Hotel is the Aqabat Jaber refugee camp, a reminder of a problem that has festered for decades.

The hotel was built in the late 1990s, when peace between Israelis and Palestinians appeared close. The hotel is next to the Oasis Casino, which opened at the same time. The casino was hugely popular with Israeli gamblers until the Israeli military prevented all Israelis from entering West Bank cities at the start of the uprising. Palestinian militants later used the building for exchanges of fire with nearby Israeli troops.

The last meeting between Israeli and Palestinian leaders on Palestinian soil was in 2000, when then-Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak held talks with Abbas’ predecessor, the late Yasser Arafat, in the West Bank town of Ramallah.

Palestinians in Jericho appeared to have low expectations from Monday’s meeting.

Mahmoud Santarisi, 35, said he would be pleased if the meeting led to the removal of one Israeli checkpoint and allowed him to visit Jerusalem, off-limits because of Israeli security restrictions.

“We hope for a good life, to be able to go to Jerusalem, to make money, and live in peace together. But Israel and the Americans will never give us a state,” Santarisi said.

Flurry of peace efforts

Monday’s meeting is part of a recent flurry of peace efforts sparked by Hamas’ takeover of Gaza in June, after a five-day rout of Abbas’ Fatah movement. The Hamas victory led Abbas to form a moderate government in the West Bank which has received broad international backing, while Hamas remains largely isolated in Gaza.

In an effort to shore up Abbas, Israel has released 250 Palestinian prisoners, resumed the transfer of Palestinian tax money and granted amnesty to Fatah gunmen willing to put down their weapons.

The efforts have also seen a visit to the region by new international Mideast peace envoy Tony Blair, an unprecedented visit by an Arab League delegation to present an Arab peace plan to Israel, and the U.S. plans for a regional conference.

In Gaza, Hamas spokesman Sami Abu Zuhri criticized Abbas for meeting Olmert, saying the meeting was “aimed at beautifying the ugly image of the Israeli occupation before the world.”

“All meetings will be of no benefit to the Palestinian people,” Abu Zuhri said.

JERICHO, West Bank - Ehud Olmert on Monday became the first Israeli prime minister to visit a Palestinian town since the outbreak of fighting seven years ago, meeting under heavy guard with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas in Jericho to talk about the creation of a Palestinian state.

Olmert took a security risk in coming to the biblical desert town, but also gave a symbolic boost to Abbas, who stands to gain stature by hosting Olmert on his own turf.

Accompanied by two helicopters, Olmert arrived by motorcade at a five-star hotel just a few hundred yards from a permanent Israeli army checkpoint on the outskirts of Jericho.

The meeting was held in one of the West Bank’s most peaceful areas. However, it still posed a challenge to Olmert’s security detail, since the West Bank cities are controlled by Abbas’ weak police forces, which in June failed to prevent Hamas militants from seizing the Gaza Strip by force.

The meeting also tested renewed Israeli-Palestinian security coordination in the West Bank, following the fall of Gaza to Hamas. The Israeli army sealed checkpoints around Jericho, while Palestinian police blocked roads around the hotel.

Conflicting expectations

The Abbas-Olmert meeting is one in a series of sessions, meant to prepare for an international Mideast conference in the U.S. in November.

However, both sides appear to have conflicting expectations.

The Palestinians hope the two leaders will sketch the outlines of a final peace deal, to be presented to the U.S. conference, Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat said Monday.

The four core issues of a future peace deal are the final borders of a Palestinian state, a division of Jerusalem, a removal of Israeli settlements and the fate of Palestinian refugees.

“What they need to do is to establish the parameters for solving all these issues,” Erekat said. “Once the parameters are established, then it can be deferred to experts” for drafting.

However, David Baker, an official in Olmert’s office, said the core issues would not be discussed now.

The leaders will discuss humanitarian aid to the Palestinians and Israeli security concerns, as well as the institutions of a future Palestinian state, Baker said.

Baker said the meeting is a signal of Israeli good will, adding that Olmert “intends for this to be a productive meeting to enable progress with the Palestinians.”

Effort to ease West Bank life

Both sides said the meeting also will deal with easing daily life in the West Bank, including the removal of some of the checkpoints erected after the outbreak of the second Palestinian uprising in September 2000.

Abbas and Olmert previously agreed to try to restore the situation to what it was before the uprising, including returning full Palestinian control over West Bank towns and cities.

However, the Israeli military has been slow to dismantle roadblocks or ease control over Palestinian towns, citing concerns that Abbas’ forces are not strong enough to prevent attacks on Israelis.

Illustrating the issue, Olmert’s motorcade passed through one of the army’s checkpoints, at the entrance to Jericho. The checkpoint was erected after the outbreak of the uprising, and has controlled Palestinian traffic in and out of the town ever since, often causing long delays for motorists.

Symbol of a bygone era of optimism

The Abbas-Olmert meeting place is surrounded by symbols of a bygone era of optimism, as well as the failures of peace talks. Across the street from the Intercontinental Hotel is the Aqabat Jaber refugee camp, a reminder of a problem that has festered for decades.

The hotel was built in the late 1990s, when peace between Israelis and Palestinians appeared close. The hotel is next to the Oasis Casino, which opened at the same time. The casino was hugely popular with Israeli gamblers until the Israeli military prevented all Israelis from entering West Bank cities at the start of the uprising. Palestinian militants later used the building for exchanges of fire with nearby Israeli troops.

The last meeting between Israeli and Palestinian leaders on Palestinian soil was in 2000, when then-Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak held talks with Abbas’ predecessor, the late Yasser Arafat, in the West Bank town of Ramallah.

Palestinians in Jericho appeared to have low expectations from Monday’s meeting.

Mahmoud Santarisi, 35, said he would be pleased if the meeting led to the removal of one Israeli checkpoint and allowed him to visit Jerusalem, off-limits because of Israeli security restrictions.

“We hope for a good life, to be able to go to Jerusalem, to make money, and live in peace together. But Israel and the Americans will never give us a state,” Santarisi said.

Flurry of peace efforts

Monday’s meeting is part of a recent flurry of peace efforts sparked by Hamas’ takeover of Gaza in June, after a five-day rout of Abbas’ Fatah movement. The Hamas victory led Abbas to form a moderate government in the West Bank which has received broad international backing, while Hamas remains largely isolated in Gaza.

In an effort to shore up Abbas, Israel has released 250 Palestinian prisoners, resumed the transfer of Palestinian tax money and granted amnesty to Fatah gunmen willing to put down their weapons.

The efforts have also seen a visit to the region by new international Mideast peace envoy Tony Blair, an unprecedented visit by an Arab League delegation to present an Arab peace plan to Israel, and the U.S. plans for a regional conference.

In Gaza, Hamas spokesman Sami Abu Zuhri criticized Abbas for meeting Olmert, saying the meeting was “aimed at beautifying the ugly image of the Israeli occupation before the world.”

“All meetings will be of no benefit to the Palestinian people,” Abu Zuhri said.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)